"By Superhuman Exertions": The Battle of Franklin

- Joseph Ricci

- Nov 30, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 17, 2020

In the late morning hours of November 30, 1864, the last elements of Maj. General John M. Schofield’s IV and XXIII Corps marched up the Columbia Pike and into the town of Franklin, Tennessee. Sergeant Samuel Libey of the 64th Ohio Infantry Regiment filed down the slope of Winstead Hill toward a line of Federal earthworks still under construction. The 64th Ohio had been on the march for the better part of a week, averaging ten to eighteen miles a day, with little time to sleep or eat. Part of the 3rd Brigade of Brig. General George Day Wagner’s 2nd Division, IV Corps, the 64th Ohio fought a series of delaying actions from Columbia, Tennessee to Franklin in effort to slow down the attacking columns Confederate General John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee. The last twenty-four hours had been among the most strenuous of the entire war.

Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield (US) and Lt. Gen, John Bell Hood (CS)

On reaching Stevens Hill overlooking Franklin, exhausted to the point of collapse, hungry to the point of frustration, Libey’s company halted to prepare breakfast. At once, a strong line of Confederates appeared and the entire division deployed into a line of battle. Wagner began withdrawing from his position but received orders from IV Corps Commander, Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley, to “reoccupy the heights and hold them unless too severely pressed” the same order instructed Wagner to “relieve Colonel Opdycke with one of your brigades and leave his and the remaining brigade as a support.”[1] Under threat of an assault, the division withdrew again first to Privet Knob and then to a small rise one-half mile south of the main Federal line. As the 64th Ohio and the rest of Conrad and Lane’s brigades filed off the Columbia Pike and into the open field, Opdycke and his brigade marched to the rear of the Federal works, where they were placed in reserve by Maj. General Jacob D. Cox, then commanding the XXIII Corps.

Brig. Gen. George D. Wagner, Col. Emerson Opdycke, and Maj. Gen. Jacob D. Cox

This relief from frontline action presented Lieutenant Colonel Porter Olson- the universally respected commander of the 36th Illinois Infantry- an opportunity for a long overdue meal and rest. Soldiers in Opdycke’s Brigade took advantage of the time to start fires to prepare food and coffee. For many of Opdycke’s men this reprieve beneath Carter Hill granted them their first opportunity for rest in three days. The 125th Ohio Regiment had been in Franklin the previous year and, recalling acquaintances made, the brigade commander ventured into town to see old friends. In the hours preceding the clash, Schofield monitored the planking of a river crossing and oversaw the withdrawal of the first of his 800 wagons. Stanley, who had been ill throughout the morning rested on the north bank of the Harpeth River and Cox rode along the semi-circular line inspecting the condition of the hastily constructed works. “From 1’clock until 4 in the evening the enemy’s entire force was in sight and forming for attack” recalled Stanley. There was little urgency behind the Federal lines because of the nature of their fortified position, “and reasoning from the former course of the rebels during this campaign, nothing appeared so improbable as that they would assault.”[2]

Along the outpost line, soldiers of 64th Ohio threw up meager barricades in anticipation of an attack. A two-mile-long battle line full of the most determined soldiers in North America started toward the exposed position. The two advanced brigades consisted of soldiers with varying degrees of experience from hardened veteran to raw recruit. Sergeant Libey, a veteran who had not yet reenlisted, found himself in a precarious situation. With his enlistment up and danger apparent, he sprang from the works “vehemently declaring that he would not submit to having his life thrown away.” Within minutes, as the forward line broke to the rear in chaos, Libey’s body lay lifeless somewhere in the path of retreat.[3]

As his guns came through the works, Corporal Alexander M. Clinton, an artillerymen in the 1st Ohio Light Artillery, shouted, "Old Hell is let loose, and coming out there." Sweeping Wagner’s two advanced brigades from their forward line, the rush was on. Brig. General Francis Cockrell’s famed Missouri Brigade followed by Maj. General Patrick Cleburne’s hardened division punched into the Federal line and forced the 100th and 104th Ohio from their position. As the Rebels poured over the earthworks, Brig. General James Reilly’s reserve line of the 8th Tennessee (US), 12th and 16th Kentucky, and 175th Ohio rushed into the breach. Those veterans of Lane and Conrad’s brigades, determined to stand and fight, joined in the melee. Still, Confederates from Maj. General William Bate’s division surged into the gap. With chaos in command of the field, Opdycke’s reserve brigade formed in the rear of the Carter House and charged forward. Lt. Col. Olson “was everywhere among his men with words of cheer and encouragement” all while exposing himself to some of the fiercest fighting of the entire war. As the desperate struggle to retake the earthworks continued, Olson fell mortally wounded near the Carter House. As he faded into unconsciousness, he uttered, “Oh help me, Lord.”[4] Col. Robert Bradshaw’s 44th Missouri (US) rushed forward to retake the first line of works. Grasping the regiment’s colors in one hand and his sword in the other, Bradshaw shouted “Come on!” Within seconds, an intense volley riddled his body with bullets and seeing their commander stuck down the Missourians retired. Over five hours of fighting, the gash in the line was restored but only by “superhuman exertions.”[5]

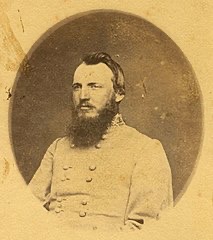

Brig. Gen. Cockrell (CS), Lt. Col. Porter Olson (US), and Col. Robert Bradshaw (US)

Such exertions are so often simplified and attributed to Opdycke’s Brigade alone. Such an oversight takes away from the gallant effort put forth by the soldiers of Lane and Conrad’s brigades that upon reaching the relative safety of the earthworks, stood and fought. To assert that Opdycke’s six regiments alone saved the day also diminishes the contribution of Brig. General James Reilly’s brigade. As the center of the line, manned by his 100th and 104th Ohio regiments broke open, Reilly’s reserve line of the 8th Tennessee Infantry, 12th and 16th Kentucky Volunteer Veteran Infantry, and the 175th Ohio rushed forward and isolated the chaos. It is proper then to attribute credit for turning the tide at the Carter property to Reilly’s men, the soldiers of Lane and Conrad’s brigades, and Opdycke’s command.

The fight raged on well into the night. From the moment Hood’s Army of Tennessee stepped off from Winstead Hill and from behind the McGavock home at Carnton, the gray ranks began to thin in the face of terrible ranged artillery. As the advance drew nearer, small arms fire peppered their lines. Dead and wounded soldiers littered the ground across that two-mile span. Struck in the right leg, the forearm, and the left shoulder, Captain J.M Hickey, of the 2nd & 6th Missouri (CS) recalled lying helplessly “in this awful condition” his uniform “saturated with blood and hundreds of dead and wounded Confederate soldiers lying almost in a heap around me...”[6] By midnight, the Federal army’s withdrawal to Nashville was underway.

The sights that the Confederates awoke to the next morning were among the most haunting of the war. In five hours, the Federals inflicted 6,000 casualties (killed, wounded, and missing) to Hood’s Army of Tennessee. Schofield recorded only 2,326 to his two corps, at least 1,000 of which came from Wagner’s division. Among the Confederate dead were six generals, six more were wounded, one was captured. The command structure of the Army of Tennessee nearly ceased to exist as did the army itself. Days later, The Morning Herald and Daily Tribune reported the death of the gallant Robert Bradshaw. Despite being wounded several times and assumed dead, Bradshaw managed to survive and lay convalescing in Franklin as Federal soldiers marched through the town on December 17 after the Battle of Nashville. Indeed, Bradshaw survived and would go on to live until 1927, dying at the ripe age of 87. November 30, 1864 was not long ago, 1927 is even closer still. It is possible that on a late fall day, standing atop Winstead Hill, at the Carter House, or in any of the small tracts of the battlefield saved by reclamation efforts, to hear the roar of battle and for a moment pause and think of the sacrifice made there that day.

[1] United States War Department, Official Record of the War of Rebellion, Series I, Volume 45, Part I (Harrisburg, PA: The National Historical Society, 1985), 231, 1174. (Hereafter referred to as O.R.) [2] O.R., 115. [3] John Shellenberger, The Battle of Franklin, Tennessee, November 30, 1864. 10 [4] The Thirty-Sixth Illinois Volunteers, 654. Carnton Collection. [5] Levi Tucker Scofield, The Retreat from Pulaski to Nashville, Tennessee, (Cleveland, OH: Press of the Caxton Co., 1909), 34; Eric Jacobson, Baptism of Fire: The 44th Missouri, 175th Ohio, and 183rd Ohio at the Battle of Franklin, (Franklin, TN: O’More Publishing, 2011), 183; Gene Schmiel, Citizen-General: Jacob Dolson Cox and the Civil War Era, (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2014), 158. [6] David Logsdon, Eyewitnesses at the Battle of Franklin, (Nashville, TN: David Logsdon, 1988), 23.

I am confused by the schematic of the battle. Didn’t Schofirld place a shortened fortified line IN FRONT of the main Union line by 100-150 yards and that shortened line was overrun by the Rebel charge? I was at the Carter House two years ago. Very lovely piece of property. Young Tod Carter, a General‘s aide, demanded to participate in the Rebel charge. He was found mortally wounded by his family and brought into the house where he died (age 23???). Franklin was worse than Picketts Charge for the South. Hood was an idiot for ordering it.

I liked the article except for the undeserving photo of Schofield. Due to his carelessness, his army should have been destroyed at Spring Hill and before the battle at Franklin, he went with the baggage trains across the river to safety while Stanley and Cox stayed to fight the battle.

Really enjoyed this article, Joseph. Well done and most informative.